It's a work night at 11:20 p.m. I'm sitting in an old "Peanuts" shirt and a gray, too-big pair of sweatpants staring at this blog post. "Shameless" plays quietly behind me. My boyfriend, Garrett, only half-paying attention, flicks through muted YouTube clips of Shinsuke Nakamura on his iPad.

11:30: Garrett stands up and absent-mindedly meanders from the couch to my workstation, glancing up from "Smackdown Live." He leans over me, examining my open notes on the "Getting Things Done" (GTD) article you're reading right now. He guides my cursor up to the top-right of my screen to a tab with a red logo.

Click.

Todoist replaces my draft. Garrett smirks at my list and kisses me playfully on the cheek. He clicks my last to-do for the day: Write article intro.

"Looks like you're done. Let's go to bed."

Todoist, like every other night for the past six months, fades to white and tells me to enjoy my night. I feel relaxed, organized, productive, and satisfied with my day.

Need help getting your tasks organized? These Todoist alternatives can help you get right on track.

It's day 752—two years and 21 days—into using David Allen's famous productivity book, "Getting Things Done." I've learned to manage my time and my stress level, when I work best and when I need a break, and what activities I can focus in on and what tasks need dedicated effort.

Here, I'm sharing the productivity method I've adopted—a customized version of GTD—which has not only become central to my workplace productivity but has become melded into my fundamental identity. I'll give you some background on GTD, some of the key lessons I learned, and show you how you can use my methodology to improve your own productivity.

Why I needed 'Getting Things Done' to save my career

When my friend, Nick, first tried to lend me David Allen's book, I didn't want to examine how I was managing my schedule. I knew it was a disaster; my priorities ranged from "quit smoking" and "read 100 classics by the time I'm 30," to short-term goals such as "write article on project management and parenting."

I knew (kinda) what I needed to get done on any given day, but task management beyond a week-to-week basis wasn't possible for me to remember. Like a half-committed dieter, I tried a host of inefficient productivity "systems" that would last a week or two at a time. For example, I'd leave unread emails in my inbox for self-reminders, spread out to-dos and research between five notebooks (I couldn't keep just one because I kept losing it), and keeping—easily—20 or 30 tabs open to "remind" myself what I needed to work on.

My productivity yo-yoed. The scale never tipped toward "delightfully efficient."

So next, I tried traditional organization methods. I created online checklists and marked up my work calendar for long-term goals (so I'd inevitably run into the task the week it was due).

After I didn't see a significant change in my workplace efficiency or satisfaction, I tried formal productivity methods, including: "Don't Break the Chain" (mark the days you work toward a specific goal; compete against yourself to make the longest "chain" of days); "Eat the Frogs First" (prioritize the hardest stuff first and do the easy stuff later); and Timeboxing (marking off specific time in my calendar to work on dedicated tasks).

With each of these methods, I found myself productive for a few days, then abandoning the system.

The ultimate consequences of these failed attempts at productivity included:

A Katrina-level messy room, trashed kitchen, and cluttered desk.

Lying to myself that I'd quit smoking "eventually," to the detriment of my teeth and my self-worth.

Chronically rescheduling appointments, from work meetings to doctors' visits.

Missed taxes, phone bills, library book return dates, and important industry application deadlines.

An inbox with over 700 unread messages.

Started projects that never got finished, even when others were relying on me.

Choosing ignorance over self-reflection, leading me to sign up for more activities than I could handle.

And that doesn't even get to the psychological effects of being disorganized. When I hit that low of disorganization, I felt...

Depressed. Why could everyone else work through their task lists when I couldn't?

Anxious. I never knew if I'd forgotten something.

Pressured. I constantly replayed my day before bed trying to remember if I'd done everything I needed to do that day.

Burdensome. I hated disappointing my coworkers—and myself—for my deadline absentmindedness.

Rushed. I felt like when I remembered a task, I had to do it right away before it disappeared from my conscious self.

Unclear. I never knew what to prioritize. My ignorance to what I could realistically get done in a day led to a cycle of procrastination and overextension. My shaky understanding of my priorities led me to feel that my stress level was unpredictable, and, worse, that severe erratic stress was normal.

Obsessed with trying to find the right productivity method, I subscribed to sites such as Inc. and the Harvard Business Review to somehow find the root of my inefficiencies.

In the past, I'd dismissed most of Nick's reading recommendations (I prefer to keep my long-form reading to fiction since most nonfiction can be summed up in an article), but Nick insisted that I read "Getting Things Done," going as far as surprising me with the book when we met for coffee.

"Trust me, Rach: it'll change your life."

I skeptically accepted the book...and promptly forgot it in my car.

Two months later (it was Saturday, April 25, 2015) Nick asked for it back. Reminded that the forgotten book was probably under the passenger car seat, I rushed to retrieve and read the manifesto before returning it to its owner.

By Sunday, the 26th, I had finished David Allen's masterpiece and felt committed—really, this time—to keeping to the "Getting Things Done" productivity method.

What is 'Getting Things Done,' and how does it work?

"Getting Things Done" is a simple idea-capturing and task-execution system that's designed to improve productivity while decluttering the mind. As one blogger put it, "[GTD] should have been called 'Getting things done in a much better way than just letting things happen, which often turns out not to be very cool at all.'"

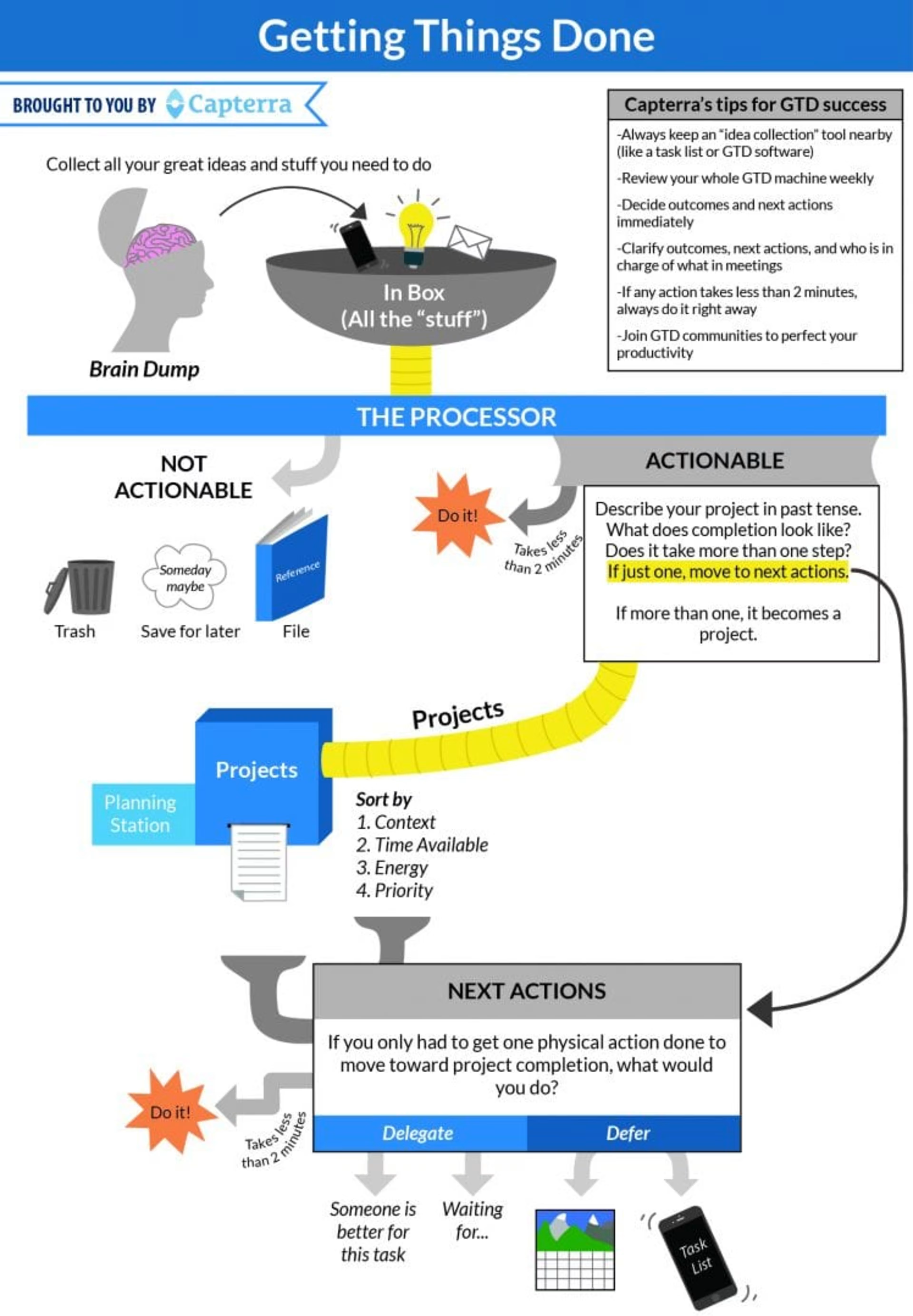

Here's how it works:

Start by writing down absolutely everything you need to do. It can be for work. It can be for family. It can be trimming your nails. Just collect all the tasks that need to get done at any point and write them down. Add to that list as more tasks come in.

That disorganized list is called the "in" list.

From there, ask yourself if it's actionable. If it isn't, dump it. (For example, if you find yourself wishing you'd learned Spanish as a child but you're in your 30s, that time has passed. Trash it. Instead, work with something actionable, like "Learn conversational Spanish for a 2020 vacation to Costa Rica.")

If it is actionable, and it takes under two minutes, do it right away!

If it's actionable but needs to get scheduled, deferred, or delegated, do so right away.

For larger tasks that require two or more steps, create project folders for them. Distill each related task into tiny to-dos, each one easy to check off, and build up to completing the project getting as a whole.

In other words, follow the graphic below.

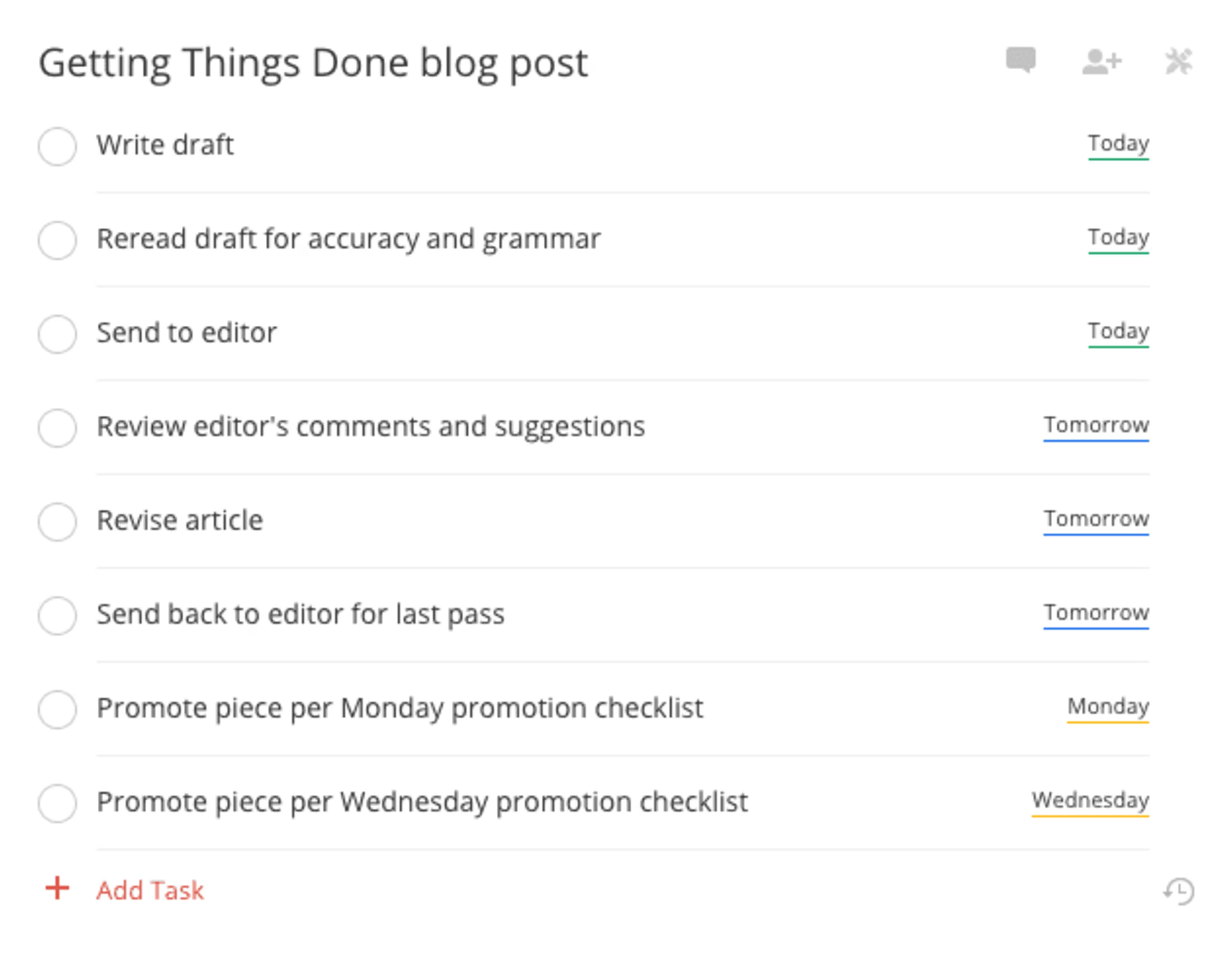

Let's look at an easy example: this blog post.

The idea of writing a blog post about my experiences with "Getting Things Done" entered my inbox. The final deliverable was actionable, would take longer than two minutes to complete, and needed to be broken down into tiny tasks.

The next thing I did was create a folder and separate out the following to-dos:

Ask people on Quora what their experiences were with "Getting Things Done" (for research and to brainstorm on my own experiences)

Create a document for drafting

Go to Google Analytics to research which keywords would best fit this article

Create the title for the piece, noting the keyword in the document so I wouldn't forget

Brainstorm and write down all lessons learned from "Getting Things Done"

Pick the five most insightful lessons and organize them by importance

Brainstorm and note important memories related to each lesson

Outline the rest of the piece

At this point, I've finished the tasks listed above, and I have many more steps to go.

When you're distilling tasks into such small moments, to-dos can easily overwhelm the GTD user. Allen recommends three ways to avoid task overflow:

Label your tasks with "contexts," e.g., tasks you can only do when you're in the city or tasks that need to be done when someone specific is present.

Use a calendar to schedule the tasks that must be completed on a certain day. Otherwise, keep all other tasks in a "next action" folder, which you can reference when you have available time.

Create "someday" and "maybe" lists for tasks that have no priority at the moment.

From there, review your tasks once a week to keep them in order. To keep your "weekly review" in check, you should:

Create a "trigger" list, which is designed to remind you of tasks that you forgot to write down. For example, my trigger list includes phrases such as "Need to get back to," "Facebook," "Check birthdays," "Vehicle repair," and a whole host of people's names, including my boss, my boyfriend, and my best friends.

Have a centralized storage area for things you need to read because reading articles and documents tends to dominate "next actions."

Use a tickler filing system, where you place physical items related to a specific month and day to remind yourself of what needs to get done.

"GTD in 15 minutes" explains the tickler filing system well:

The idea is that you can place physical items you will need on a specific day (tickets for the concert), reminders of things you possibly want to do on a specific date (remember, the calendar is only for things that have to be done on a specific date/time), or the notes from the lecture you didn't really understand (“I will want to review these in a week when my subconsciousness has chewed on it for a while"). Every day when you get up, you open the folder with the current date. You then pocket your concert tickets, decide that you do want to take the dog to the dog hairdresser today, but push the lecture notes back three days since you don't have time right now. Having emptied the folder, you place it in the back, bringing tomorrow's folder to the front. At the end of each month, you open the folder for the new month and deal with its contents—like putting items in the correct day folders.

If this looks like a lot of information, that's because most explanations of "Getting Things Done" are too simple.

Allen's book has over 200 pages of research and justification for why this system works, how to use it well, and why you should consider using it in your life. It will always do a far better job of explaining Allen's method than I ever could, so I do suggest picking it up.

A brief disclaimer for the faithful

The five lessons from "Getting Things Done" that I outline below come entirely from my personal experience. The GTD framework above is David Allen's by-the-book recommendation—my years of using the methodology have blended his model into one that works for me.

Some people may find it useful to follow the GTD methodology exactly. What I'm sharing here will hopefully benefit others. It's possible others have done what I've done, but in a different way, and I'd love to hear about your GTD processes in the comments section at the end of this article.

Without further ado, my top five lessons from implementing "Getting Things Done" over the past two years.

1. Life and work don't 'balance.' They 'blend.'

Before using "Getting Things Done," I lived under the assumption that productivity at work was somehow different from productivity at home.

Growing up, my Dad traveled a lot for business. He would disappear for a few days, returning with gifts from strange cities and foreign countries. He brought home treasures such as nesting dolls, Hungarian chocolates, and, once, a Smash Mouth t-shirt from San Jose.

But it wasn't the gifts that Dad brought home that made me so happy to see him. He'd put down his laptop bag, take off his coat, set down his wallet and class ring on the kitchen counter, and then power down his brick of a phone (Dad was an early adopter to BlackBerry, and it took him way too long to get over it).

The phone would chime as it died, signaling playtime—time to have Dad's undivided attention. Work was over. Life began. I imagined that my work life would be the same when I grew up.

Now, as a working professional, I have tried the "work-life balance" thing, and it's inefficient and unenjoyable. With "Getting Things Done," I realized that I was chasing the fantasy of a bygone work era, when LinkedIn, Facebook, work email, and Candy Crush weren't all equally competing for your attention on your handheld personal device. Before "Getting Things Done," At home, I felt as though I only needed to write down chores in the event of a cleaning spree.

But no more. That work—yes, housework is work, along with remembering to call Mom or buy birthday gifts—gets written down and scheduled just like anything I have to do for my job.

In a way, "Getting Things Done"—the 2001 version that Allen initially described (I haven't read the update)—made me realize that it didn't matter where I was expending my effort, just that I was expending it at all.

The method forces you to write down anything that may be a task for your "in" box. In my last review for me, that included:

Email Daniel back and thank him for his report (Work)

Buy cat food (Home)

Reread Saga Deluxe Edition book one (Pleasure)

Confirm [business trip] details with Lisa (Work)

Vacuum the couch (Home)

Read "The Step-by-Step Guide to Syndicating Content (Without Screwing up Your SEO)" (Work)

These are all things I want and need to do, and my brain doesn't magically compartmentalize which tasks are for "work" or "other." I learned to schedule out what I needed to do in a day—everything, from grocery shopping to evaluating crosstabs—to make sure I didn't get burned out at work or at home.

When I first started with "Getting Things Done," I had my to-do list up on my second monitor at work and that was it. The app I was using (which I later ditched—more on that later) didn't even work on my phone. When I left the office for the day, I left my to-do list there too.

The consequences?

As much as I didn't want to think about work at home, I'd occasionally get bursts of creativity. I told myself I'd remember it when I got back into the office, but I'd inevitably forget it over the next 16 hours. That, or I'd obsess over remembering the idea to the point of not being able to enjoy my night.

I realize that this example exemplifies why Allen emphasizes writing all ideas down, but to me, it symbolizes something much greater: You can't control when an idea will come to you. I thought of the perfect holiday gift for my boyfriend during a staff meeting, and I came up with a $13 million dollar initiative for Capterra's site at 2 a.m. on the Saturday before Mother's Day.

Trying to partition "Getting Things Done" to my work life alone was a mistake. It's now fully integrated into my life, and I'm happier and more productive for it.

2. Plan for your plans.

One of the biggest mistakes that people make when first trying "Getting Things Done" is not breaking down their tasks into small enough "next actions." I, too, initially fell victim to that common challenge.

My favorite story about someone getting stuck on "next actions" comes from Drew Carey (yes, that Drew Carey of The Price is Right). Carey hired David Allen to sort out his mess of personal productivity personally. His story, which appears in another pop-psychology book called "Willpower," goes like this:

By going through all the paperwork, all the unanswered e-mails, all the other unfinished tasks in his computer or on his mind, Carey identified dozens of personal and business projects, which was typical. Allen's clients usually have between 30 and 100 projects, each with at least a couple of tasks, and they spend a full day or two to complete the great initial purging and sorting and processing. After Carey identified the projects, he had to single out the specific Next Action for each project... As Carey worked through all the stuff, Allen sat in his office all day long. “He'd honestly sit there and watch me do my-emails," Carey says. “Whenever I'd get stuck he'd say, 'What's going on?' And I'd tell him, and he'd go, 'Do this.' And I would do it. He was very decisive about it. There would be only a few times when he'd say, 'It could be a this or a that. What are you going to do with it?'...

If you're not cringing at the thought of having 100 projects that you need to break up into each action, you haven't been reading closely enough. Even this simple blog post took 16 separate to-dos, and, as Carey implies above, it's easy to get stuck figuring out what that next task is.

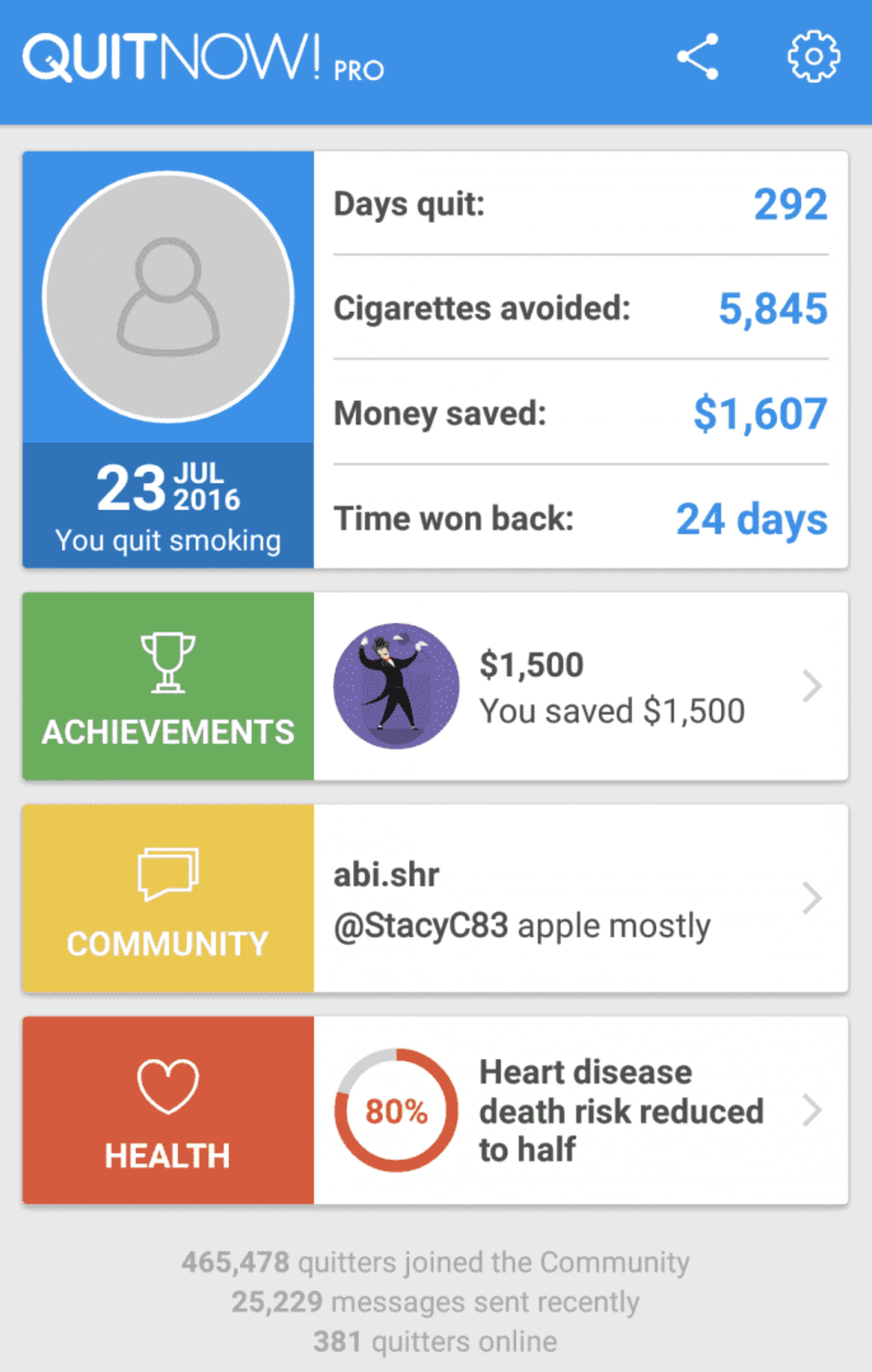

In fact, when using "Getting Things Done" correctly, identifying next actions becomes the hardest part of the system. Users will regularly be tempted to take shortcuts. For example, I (successfully!) used "Getting Things Done" to quit smoking. But it wasn't successful right away.

Why?

My action item was:

Quit smoking.

I figured that because the only action I had to take was inaction, quitting smoking would be a singular, willpower-charged task that I could complete in one day.

Ha!

Turns out that quitting smoking took a number of action items, and it was a huge project. It took me over a year to figure out all the little things I needed to do to finally quit.

My actual task list could be distilled to something like this. (Arguably, some of these "tasks" were projects unto themselves. I've filtered out the various "quit-cold-turkey tasks" that I periodically set for myself, which simply didn't work):

Create a folder in Chrome to bookmark favorite articles on quitting smoking.

Research affordable ways that other 20-something smokers used to quit.

Look at nasty pictures of eroded smoker teeth to maintain motivation (weekly).

Join online support groups for people who want to quit smoking who are close to me in age.

Observe and take notes on the struggles others like me were having and how the community helped get them through their cravings.

Choose a new method of quitting.

Taper down (weekly).

And when that didn't work (not all quitting methods work for everyone), I looped:

Choose a new method of quitting.

Order the helpful book most commonly mentioned in the forum off of Amazon: "Allen Carr's Easy Way To Stop Smoking."

Read chapters one through 14 of Allen Carr's book (Saturday).

Journal about reading chapters one through 14 of Allen Carr's book (Saturday).

Finish Allen Carr's book (Sunday).

Journal about finishing Allen Carr's book (Sunday).

Download QuitNow! PRO to track cigarettes not smoked (Sunday).

Empty ash tray and throw it away (Sunday).

Take out the trash (Sunday).

Throw away purse cigarettes (Sunday).

Throw away living room cigarettes (Sunday).

Throw away bedroom cigarettes (Sunday).

Throw away car cigarettes (Sunday).

Text close friends that I'd quit smoking. Ask for their support (Sunday).

Throw away work cigarettes (Monday).

Check QuitNow! Pro (Daily).

Write an email to parents and brothers to inform them that I quit and ask them out to dinner to celebrate (Friday).

Formally call myself an ex-smoker (three months later; complete project).

That's a whole lot more than just "quit smoking," right?

But by breaking down each step into tiny tasks, I was finally able to kick that terrible, nasty habit. I stopped smoking on July 23, 2016, and haven't looked back since.

That project is done.

Creating those small tasks made quitting smoking so much easier than relying on willpower alone. Each step felt logical—natural, even—making the beast of "quitting smoking" far more manageable.

One could even argue that "Getting Things Done" saved my life.

While kicking the nicotine habit is a more extreme example of breaking projects down to simple, actionable tasks for the sake of sanity, it personifies the importance of sticking to Allen's prescription of spending the time to lay out how you'll take on each project.

Drew Carey agrees:

"Before, I'd see a pile of papers and wouldn't know what the hell was in them and just be like, 'Oh, my God,' Carey says. 'The day I got to zero, which is GTD talk for having nothing in your in-box—no phone messages, no emails, nothing, not a piece of paper—when I got to that point, I felt like the world got lifted off my shoulders. I felt like I had just come out of meditating in the desert, not a care in the world. I just felt euphoric.'"

That feeling of euphoria leads me to my next lesson learned: increased efficiency is good for mental health.

3. Productivity and happiness are intertwined.

Above, you read about how I struggled with productivity.

How I was late with assignments.

Late meeting friends.

Forgetting important dates.

Feeling unproductive and rushed, all at the same time.

Without a formal task management system, I felt pretty bad about myself.

There's a lot of research that substantiates the idea that lowered self-worth is tied to low efficiency, though I maintain that cause and effect remain dubious in avi research. Sure, poor mental health can cause a decline in productivity, but can an uptick in productivity improve mental health?

Ready to get things done? Explore productivity software solutions to help you efficiently manage your tasks.

From my experience with "Getting Things Done," the answer is a resounding "Yes!" As of now.

For me, the reason why is common sense: If you find worth and meaning in your work, and you're able to get more done out of the day, then, of course, you'll feel better about yourself.

Allen, of course, takes it a step further.

Consider the introduction to his TEDx Talk:

(The full transcript is also available.)

The quote that stands out to me the most?

I use a martial arts term which is 'mind-like water.' A body of water responds to physical forces around it totally appropriately. It doesn't overreact, it doesn't underreact. You throw in a pebble. It does pebble [sic]. Back to calm and balanced again. You throw in a boulder. What does it do? It does boulderness [sic]. It does it very dispassionately. It doesn't tense up of what the rock hits it. It doesn't get all mad at the rock for having disturbed its calmed life. Back to calm and balanced again.

When your life is organized, you are able to appropriately react to new stimulants—whether it's calmly finishing a report you've known about for months or rushing to pick up your sick loved one from school. Reactions to emergencies are reserved for emergencies only, instead of constantly reflecting on an ambiguous to-do list that you're trying to recall from memory.

That would instill panic in anyone. I'm surprised we don't hear of therapists recommending 'Getting Things Done' more often. I'm willing to bet that it would make some of their clients feel better.

Of course, my evidence is purely anecdotal and probably a symptom of being in a high work-ethic culture, but I'm willing to bet money that this lesson learned doesn't only apply to me. Let me know in the comments if you've experienced this effect from GTD as well.

4. No productivity tool can fix a broken system on its own.

I'm not just a blogger.

I'm not just a tech blogger.

I'm not just a productivity tech blogger.

I am a blogger who reviews and writes about project management software and task management software for a living.

I have been exposed to a whole host of productivity tools designed to improve your personal productivity. I'm talking about testing products that you've probably tried yourself, including Trello, Asana, Trigger, Taskworld, and Remember the Milk, on a regular basis. I started working with this kind of software about a year before reading "Getting Things Done."

Trust me. I know what these products promise and what they can really do.

These productivity tools are great when they're used correctly—but figuring out how to use them right is the toughest part of implementing a new efficiency management system.

When learning how to use "Getting Things Done," I blew through a number of free GTD software options.

The first was Producteev, which, to be very clear, _I wouldn't not recommend using because it hasn't been updated in almost four years, which poses a major cybersecurity risk_. Add to that, the system was slow and I overwhelmed it with mislabeled projects.

Producteev worked as a starter app, but I quickly ditched it for Wrike.

Wrike is a tool that I could, at this point, return to and be happy with. I made two mistakes with Wrike. First, I played with its advanced options, even though I only intended to use its freemium version, so when the advanced trial ran out I could feel the effects of depleted functionality. Second, I started to manage some team projects on the system, which, in my mind, transferred Wrike into a "work" tool instead of a "Rachel" tool. I moved on.

Like Cinderella's slipper, Todoist fits me perfectly—to the point where I happily pay just under $30 a year for Todoist Premium. The app is mobile-first, which makes it ideal for capturing ideas on the go, and isn't so feature heavy that I get overloaded when using it.

However, I'm confident that had I tried Todoist first, I would have ended on a different tool. There are plenty of great task tools for "Getting Things Done," but none of them are useful if you don't use the system correctly.

5. Humans and systems have limits.

I don't use contexts.

I ditched the "someday" folder in my first six months.

I never created a "maybe" folder.

I schedule all my tasks, not just the ones that have firm due dates, except those that go on my bucket list.

I maintain a bucket list in the first place.

What I've found is that the GTD methodology doesn't work perfectly for me. And that's okay, especially since I've learned to understand the most effective parts of it for me:

capturing ideas

breaking up projects

the two-minute rule

weekly review

I found the context cues distracting, as I spend most of my time between a handful of places (work, car, and home) unless I'm going somewhere for a specific purpose (for example, the grocery store or the mall).

As I've used GTD over the past few years, I've learned that trying to stick strictly to the methodology is more stressful than helpful for me. I've learned to keep the good and ditch the extraneous.

More lessons from 'Getting Things Done'?

I don't know all the answers to what makes GTD work or not work, but I do know that this productivity method has been a life and career-saver for me. I know when I should be focusing on work when I should be watching Shameless, and when it's time to go to bed.

I'd love to hear your reactions to this article. Have you used or considered using "Getting Things Done"? What have your experiences been? Do you agree or disagree with my takeaways? Why? What tools do you use?

Definitely, leave a comment below and I'll respond.

If you're interested in productivity tools, you might also want to read...