In many ways, business is nothing more than math as a spectator sport. It’s like if you dumped the entire Wharton School of business on a soccer pitch and then threw a bunch of Monopoly money out there.

Actually, that sounds really fun.

Anyways, unless you have a very odd sort of business, you can probably break it down into a series of basic math problems. That might not be what you want to do, but it’s something that you could do.

As basic as that may sound, it somehow always seems complicated. Knowing some of the fundamentals of business math will help you stay ahead of the competition.

Today, we’re going to cover the basics of margins, what your cost of goods really entails, and how to calculate and understand cash flow. If you’re still with me, we’ll jump into compound interest. Then we’ll finish off with a little discussion on why all this math stuff might be incredibly overrated.

Who could ask for more?

Gross margins and its calculation

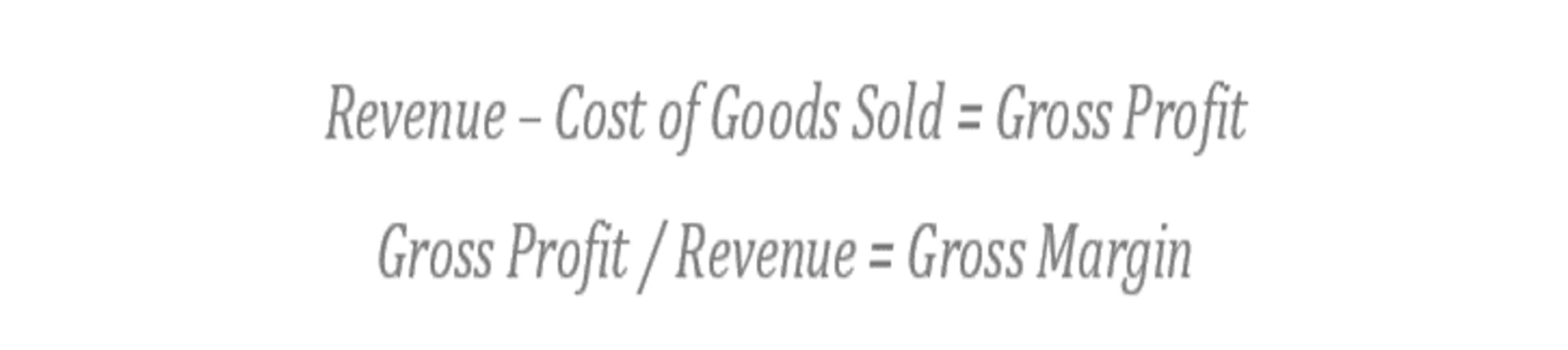

When businesses release their quarterly or annual earnings, people tend to focus on the various margins. The two most often-referenced margins are the “gross margin” and the “profit margin.” The two reference different portions of the income statement and tell you very different information about how a business is being managed.

Gross profit appears fairly high up on the income statement. It refers to the amount of money that remains after you take out the cost of goods sold – more on this later.. That value divided by the total amount of revenue earned gives you a percentage called gross margin.

The movement of the gross margin over time tells you how effective your branding and sales techniques are. It can also tell you something about how well you’re managing inventory levels.

Here’s an example. Ping Pong USA (PPU) sells 100 ping pong balls for $100 this month. To make the ping pong balls, it spends $50. That means that, after the cost of goods sold is taken out, it has $50 left in gross profit. $50 divided by $100 (the original revenue) is .50 or 50%. This month, PPU’s gross margin is 50%.

Next month, PPU’s demand is much lower, but it thought sales would be going up, so it made extra balls. Now, it has extra inventory and lower demand. To increase its sales, PPU has to put balls on sale. It ends up selling 120 balls, but only brings in the same $100. To make the 120 balls, it spent $60.

In this month, the company’s gross margin is $40 -- $100 - $60 = $40 and $40 / $100 = .40 or 40%.

A fall in gross margin can highlight problems with sales strength. If your company demands a high premium – like a luxury brand – then you can keep your margins higher. If people start to undervalue your brand, then gross margins are likely to fall.

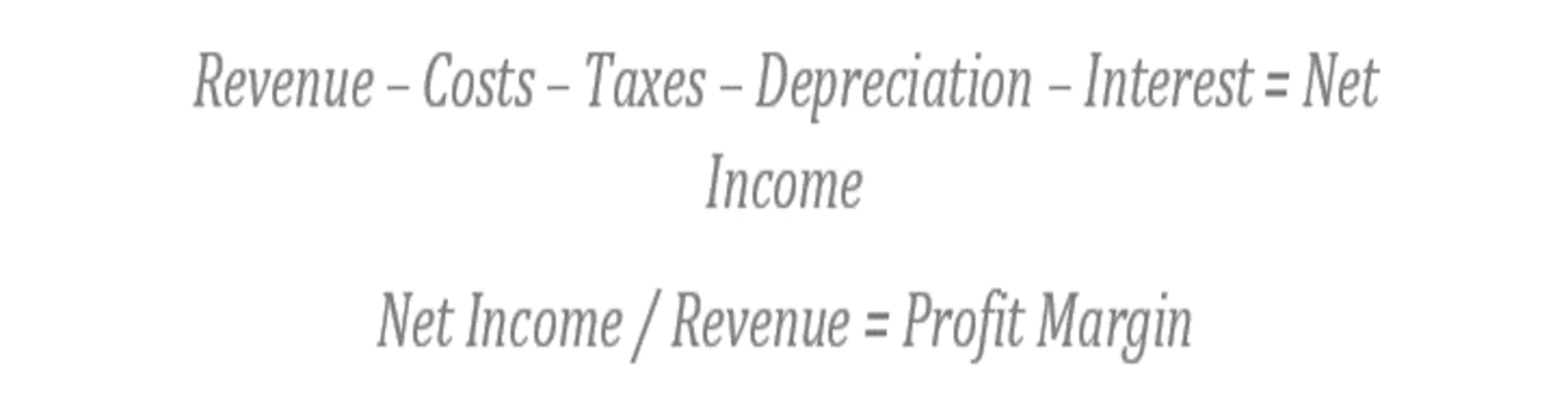

Profit margin

Profit margin comes from the final line in an income statement, usually labeled “net income.” Net income is the real “bottom line” and it represents everything leftover after all costs have been taken out of revenue.

Just like gross margin, profit margin is a measure of effectiveness – sort of. While we talk about the bottom line, and it’s super important, it’s not everything. In fact, net income is oddly overrated. First let’s look at it, then we can talk about what flaws it has.

This may look straightforward, but let’s think about the terms a bit. Revenue is simple enough, it’s all the money we made in the quarter – or year or whatever. Cost, on the other hand, is a tricky little wicket.

When we think of costs, we usually think of all the things that we have control over every day – salaries, rent, utilities, staples, the occasional six-foot-long sub, you know, costs. In reality, costs also include taxes, the depreciation of assets, and any interest that your company pays on loans.

This means that you might have odd shifts in net income – and therefore your profit margin – without doing much differently on the operational level. Instead of profit margin, maybe we could figure out something else. Something that focuses on our operations instead. Hmmm.

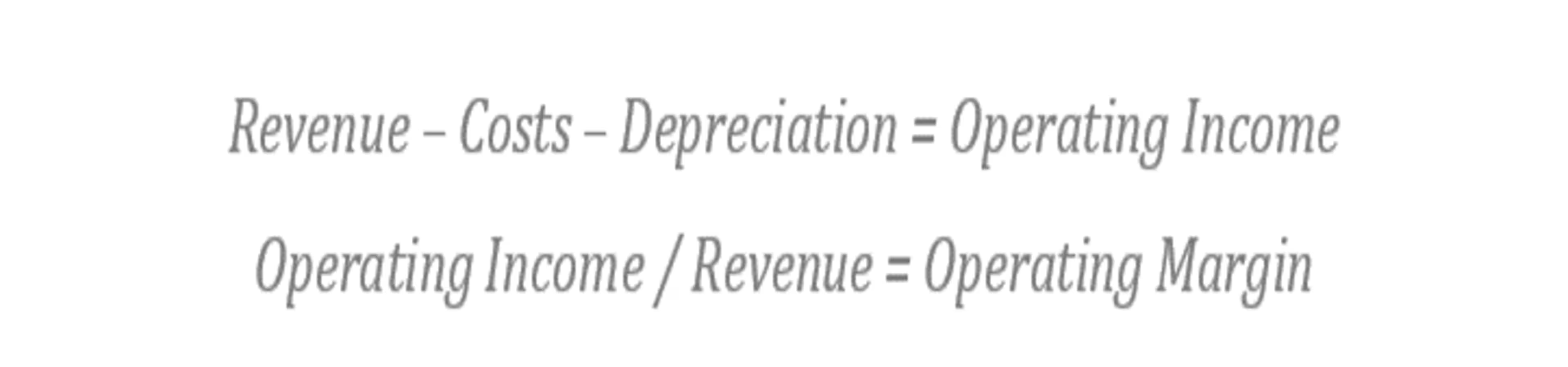

Operating margin

Yeah, there’s a thing called operating margin and yes, that lead up was over the top. That doesn’t matter now. What matters is that operating margin can give you most of the benefits of profit margin without the drawbacks of including costs that shift underneath you.

Operating margin skips out on counting the costs associated with interest and taxes, which gives you a better idea of how well your business is doing, without worrying about the things that may change without your control. The equation for operating margin is:

You can see that we end up keeping depreciation in the formula, as it’s something that we have – some – control over. Looking at the change in your operating margin over time can actually give you a great insight into how effectively your business is running.

It’s especially useful when used in tandem with some other margins, like gross margin. If you see, for instance, that your gross margin is holding steady, but your operating margin is rising, you might be able to infer that your back office operations are becoming more efficient.

Cost of goods sold

When we first got into this discussion, we mentioned the cost of goods sold. This is a more complex equation than it would seem on the surface. Think back to PPU’s operation. If we’re selling a ping pong ball – and the key term here is “selling” – what costs are involved?

Well, first we need to build the thing, so we need to add in the cost of the plastic. We don’t turn raw material into ping pong balls without effort, so we’ll need to include labor and equipment costs. Now we’ve got a ball sitting at the end of the production line. Great. Let’s sell it.

Hold on there cowboy – we’re not going to just open the shop room doors and let the punters in. We need to move all these things from production to sales. So we need to ship the ping pong balls and add that cost to the total cost of goods sold.

Finally, we’ve got the balls at the store. To sell them we’ve got to pay sales folks and take on the costs associated with sales. Putting all that together, we end up with:

With this value in mind, you can better price your products and services. You can also make smarter choices about investments, as you’ll be paying closer attention to the real costs associated with getting your product into a customer’s hand.

Compound interest

Great, we’re done with the basics. You can now look at your business with a new pair of eyes and get some ideas on how to make things run more efficiently. Let’s take a look at two more financial concepts that business owners would do well to understand.

Compound interest is a beautiful thing. If you have any interest in borrowing or investing, compound interest is going to be the key to financial success. Before we dive in, we should take a second to talk about interest in general.

Interest refers to a percentage of a value, added to the value on some time basis. For instance, you might lend your friend $100 with the assumption that he would pay you back $105 later on. You, in effect, were charging him 5% interest -- $105/$100 = 1.05.

In finance, interest is – supposed to be – a measure of risk. When you invest in a failing company, you expect to get more money back for your cash, due to the fact that they might go under and you could lose everything. Conversely, when you lend money to your bank by putting it in your savings account, the bank pays you very little, as it’s considered a safe place.

But seriously, normally interest is linked to risk. Compound interest is the way you get rewarded for taking risk over a period of time.

With normal interest, you just get paid a percentage on a recurring basis. This is how classic bonds work. You buy a bond for $1,000 – your investment – and every year or six months, you get to collect some percentage of the investment. Then, at the end of five years, you get your investment back. Tada!

With compound interest, the interest that you’re paid gets added to the original investment amount and interest is then paid on the new total. So if you invest $1,000 and get 10% interest over three years, the final total paid to you will be:

$1,000 * 1.1 = $1,100 * 1.1 = $1,210 * 1.1 = $1,331

If you had used simple interest, you would have only received $300 – three payments of $100 – over the same time frame.

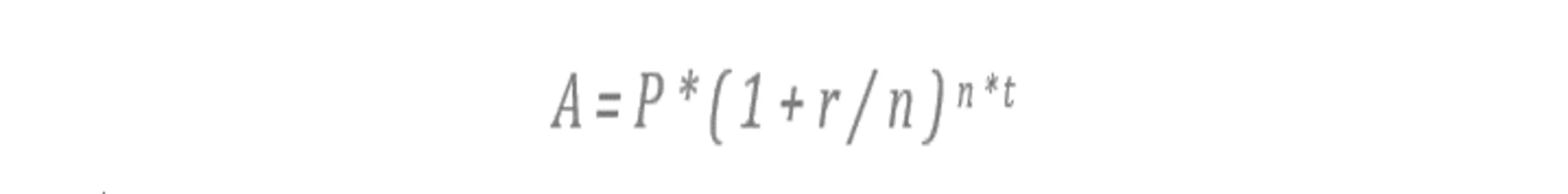

Compound interest is how you turn relatively small sums of money into retirement plans. It’s also how you turn $5,000 in credit card debt into $10,000, so watch out for it. Here’s the formula for compound interest:

You weren’t expecting that, I can tell. It might look crazy, but it’s pretty straight forward. You’re trying to figure out “A,” which is the total amount you’ll be paid – or owe, if you’re borrowing.

You start with “P,” the principal or initial investment. Then, you multiply it by one – which represents 100%, your starting position – plus the result of the interest rate as a decimal “r” divided by the number of payments “n” per unit of time.

This little segment is important because you might be quoted an annual percentage rate, but interest might actually accrue on a monthly basis. That means that you need to break that interest rate down into its individual payments.

You take the resulting number and raise it to the power of the number of payment per time period “n” multiplied by the number of time periods “t.” This gives you the total number of payments.

For our previous example, we would then have:

A = 1,000 * ( 1 + .1/1) 1 * 3

A = 1,000 * ( 1 + .1 ) 3

A = 1,000 * ( 1.1 ) 3

A = 1,000 * 1.331

A = 1,331

Just like that.

The lies my math book taught me

Way back at the start of this, we talked about how business is basically math. That’s true and it’s not. Running a business is more than just plugging in the right numbers. The Office’s Michael Scott once said, “Business is always personal. It’s the most personal thing in the world.”

Math, on the other hand, is completely impersonal. Here: 320,289,069 + 3,942,000 + 2,866,909 = 321,364,160. That’s the total population of the US at the start of 2015, the beautiful baby born every eight seconds, the life clipped off by death every eleven seconds, and the resulting population at the end of the year. It’s impersonal and it’s math.

The plans you’ll make to increase margins and to get more from your investments will all go south, at some point. You’ll lose an employee or get a bad batch of some material or have a train shipment derail or a customer go out of business. If you’re relying solely on the equations you’ve picked up along the way, your business will suffer.

The best plans are personal and flexible. You can use these tools to give yourself a better understanding of your business, but you’ll never have a great business if you only use these tools.

I’d love to know how you use math in your business and how you keep yourself free of its tyranny. Drop me a line in the comments below, and good luck out there.